5 Designing Effective Tables

You are reading the free online version of this book. If you’d like to purchase a physical or electronic copy, you can buy it from No Starch Press, Powell’s, Barnes and Noble or Amazon.

In his book Fundamentals of Data Visualization, Claus Wilke writes that tables are “an important tool for visualizing data.” This statement might seem odd. Tables are often considered the opposite of data visualizations such as plots: a place to dump numbers for the few nerds who care to read them. But Wilke sees things differently.

Tables need not — and should not — be data dumps devoid of design. While bars, lines, and points in graphs are visualizations, so are numbers in a table, and we should care about their appearance. As an example, take a look at the tables made by reputable news sources; data dumps these are not. Media organizations, whose job it is to communicate effectively, pay a lot of attention to table design. But elsewhere, because of their apparent simplicity, Wilke writes, “[tables] may not always receive the attention they need.”

Many people use Microsoft Word to make tables, a strategy that has potential pitfalls. Wilke found that his version of Word included 105 built-in table styles. Of those, around 80 percent, including the default style, violated some key principle of table design. The good news is that R is a great tool for making high-quality tables. It has a number of packages for this purpose and, within these packages, several functions designed to make sure your tables follow important design principles.

Moreover, if you’re writing reports in R Markdown (which you’ll learn about in Chapter 6), you can include code that will generate a table when you export your document. By working with a single tool to create tables, text, and other visualizations, you won’t have to copy and paste your data, lowering the risk of human error.

This chapter examines table design principles and shows you how to apply them to your tables using R’s gt package, one of the most popular table-making packages (and, as you’ll soon see, one that uses good design principles by default). These principles, and the code in this chapter, are adapted from Tom Mock’s blog post “10+ Guidelines for Better Tables in R.” Mock works at Posit, the company that makes RStudio, and has become something of an R table connoisseur. This chapter walks you through examples of Mock’s code to show you how small tweaks can make a big difference.

Creating a Data Frame

You will begin by creating a data frame that you can use to make tables throughout this chapter. First, load the packages you need (the tidyverse for general data manipulation functions, gapminder for the data you’ll use, gt to make the tables, and gtExtras to do some table formatting):

As you saw in Chapter 2, the gapminder package provides country-level demographic statistics. To make a data frame for your table, you’ll use just a few countries (the first four, in alphabetical order: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, and Angola) and three years (1952, 1972, and 1992). The gapminder data has many years, but these will suffice to demonstrate table-making principles. The following code creates a data frame called gdp:

gdp <- gapminder %>%

filter(country %in% c("Afghanistan", "Albania", "Algeria", "Angola")) %>%

select(country, year, gdpPercap) %>%

mutate(country = as.character(country)) %>%

pivot_wider(

id_cols = country,

names_from = year,

values_from = gdpPercap

) %>%

select(country, `1952`, `1972`, `1992`) %>%

rename(Country = country)Here’s what gdp looks like:

# A tibble: 4 × 4

Country `1952` `1972` `1992`

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Afghanistan 779. 740. 649.

2 Albania 1601. 3313. 2497.

3 Algeria 2449. 4183. 5023.

4 Angola 3521. 5473. 2628.Now that you have some data, you’ll use it to make a table.

Table Design Principles

Unsurprisingly, the principles of good table design are similar to those for data visualization more generally. This section covers six of the most important ones.

Minimize Clutter

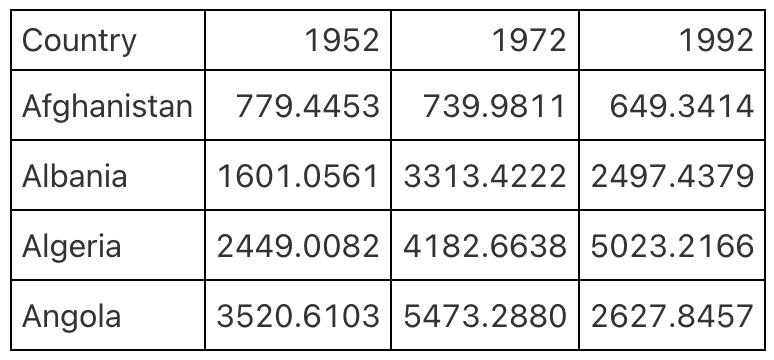

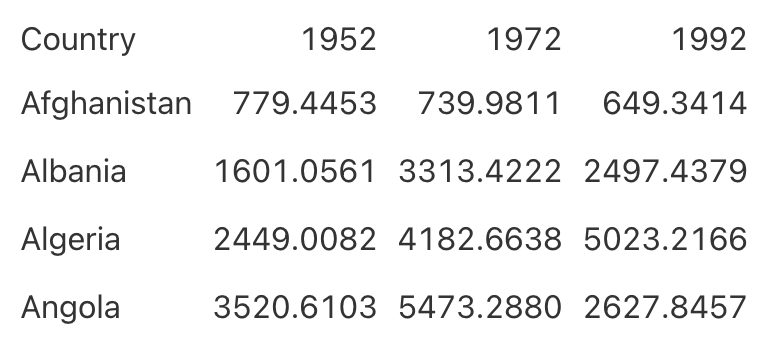

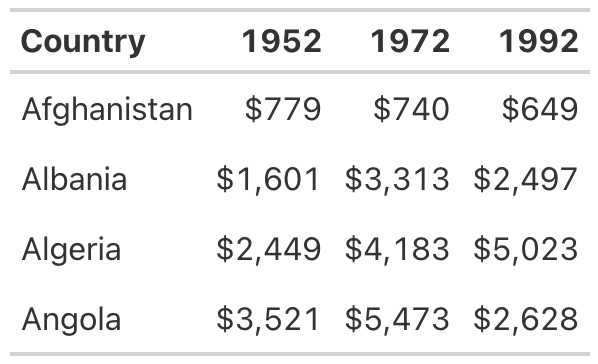

You can minimize clutter in your tables by removing unnecessary elements. For example, one common source of table clutter is grid lines, as shown in Figure 5.1.

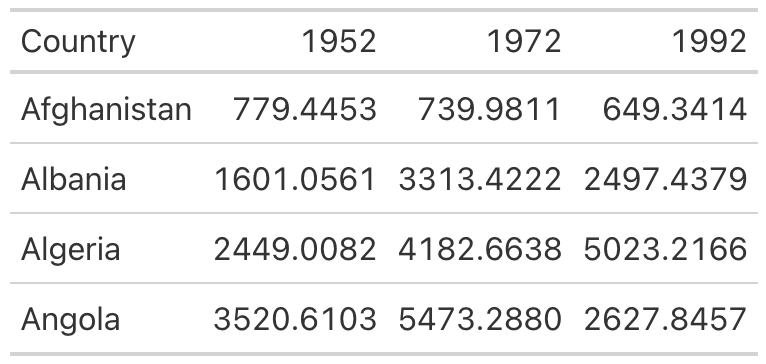

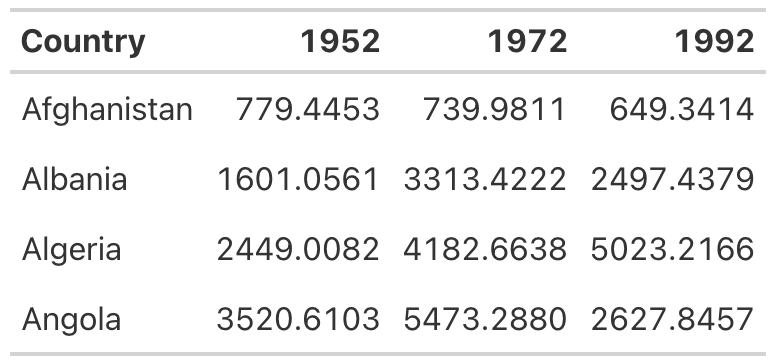

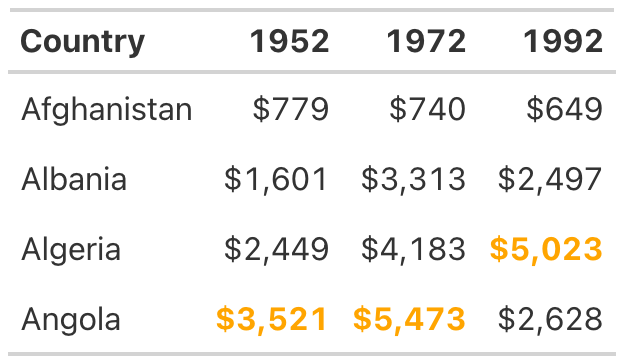

Having grid lines around every single cell in your table is unnecessary and distracts from the goal of communicating clearly. A table with minimal or even no grid lines (Figure 5.2) is a much more effective communication tool.

I mentioned that gt uses good table design principles by default, and this is a great example. The second table, with minimal grid lines, requires just two lines of code—piping the gdp data into the gt() function, which creates a table:

To add grid lines to every part of the example, you’d have to add more code. Here, the code that follows the gt() function adds grid lines:

gdp %>%

gt() %>%

tab_style(

style = cell_borders(

side = "all",

color = "black",

weight = px(1),

style = "solid"

),

locations = list(

cells_body(

everything()

),

cells_column_labels(

everything()

)

)

) %>%

opt_table_lines(extent = "none")Since I don’t recommend taking this approach, I won’t walk you through this code. However, if you wanted to remove additional grid lines, you could do so like this:

gdp %>%

gt() %>%

tab_style(

style = cell_borders(color = "transparent"),

locations = cells_body()

)The tab_style() function uses a two-step approach. First, it identifies the style to modify (in this case, the borders), then it specifies where to apply these modifications. Here, tab_style() tells R to modify the borders using the cell_borders() function, making the borders transparent, and to apply this transformation to the cells_body() location (versus, say, the cells_column_labels() for only the first row).

Running this code outputs a table with no grid lines at all in the body (Figure 5.3).

Save this table as an object called table_no_gridlines so that you can add to it later.

Differentiate the Header from the Body

While reducing clutter is an important goal, going too far can have negative consequences. A table with no grid lines at all can make it hard to differentiate between the header row and the table body. Consider Figure 5.4, for example.

By making the header row bold, you can make it stand out better:

table_no_gridlines %>%

tab_style(

style = cell_text(weight = "bold"),

locations = cells_column_labels()

)Starting with the table_no_gridlines object, this code applies formatting with the tab_style() function in two steps. First, it specifies that it wants to alter the text style by using the cell_text() function to set the weight to bold. Second, it sets the location for this transformation to the header row using the cells_column_labels() function. Figure 5.5 shows what the table looks like with its header row bolded.

Save this table as table_bold_header in order to add further formatting.

table_bold_header <- table_no_gridlines %>%

tab_style(

style = cell_text(weight = "bold"),

locations = cells_column_labels()

)Align Appropriately

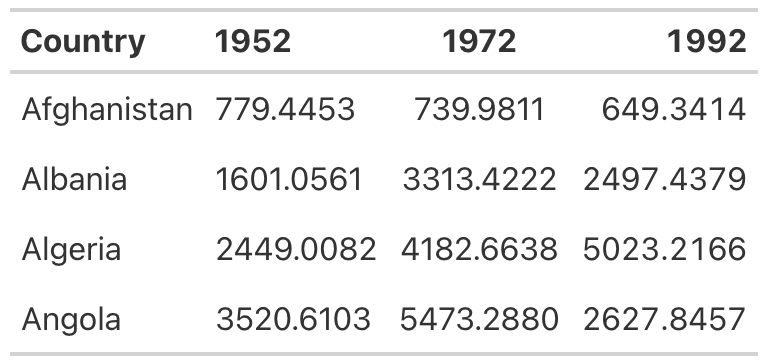

A third principle of high-quality table design is appropriate alignment. Specifically, numbers in tables should be right-aligned. Tom Mock explains that left-aligning or center-aligning numbers “impairs the ability to clearly compare numbers and decimal places. Right alignment lets you align decimal places and numbers for easy parsing.”

Let’s look at this principle in action. In Figure 5.6, the 1952 column is left-aligned, the 1972 column is center-aligned, and the 1992 column is right-aligned.

You can see how much easier it is to compare the values in the 1992 column than those in the other two columns. In both the 1952 and 1972 columns, it’s challenging to compare the values because the numbers in the same position (the tens place, for example) aren’t aligned vertically. In the 1992 column, however, the number in the tens place in Afghanistan (4) aligns with the number in the tens place in Albania (9) and all other countries, making it much easier to scan the table.

As with other tables, you actually have to override the defaults to get the gt package to misalign the columns, as demonstrated in the following code:

table_bold_header %>%

cols_align(

align = "left",

columns = 2

) %>%

cols_align(

align = "center",

columns = 3

) %>%

cols_align(

align = "right",

columns = 4

)By default, gt will right-align numeric values. Don’t change anything, and you’ll be golden.

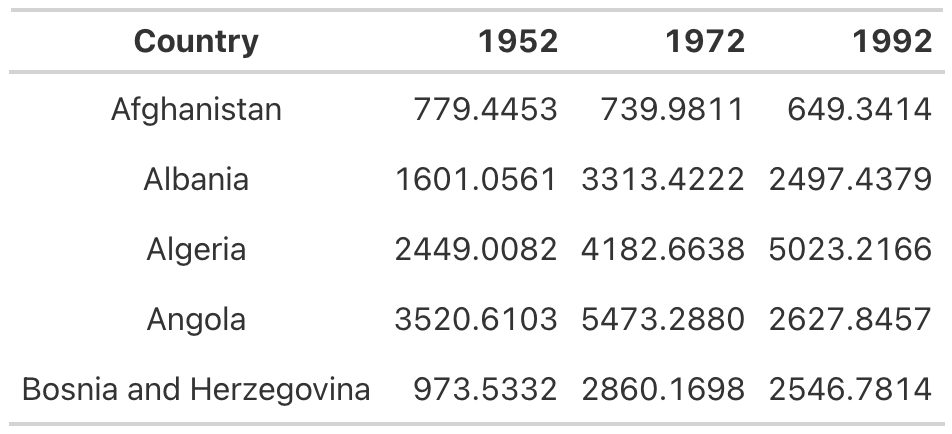

Right alignment is best practice for numeric columns, but for text columns, use left alignment. As Jon Schwabish points out in his article “Ten Guidelines for Better Tables” in the Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis, it’s much easier to read longer text cells when they are left-aligned. To see the benefit of left-aligning text, add a country with a long name to your table. I’ve added Bosnia and Herzegovina and saved this as a data frame called gdp_with_bosnia. You’ll see that I’m using nearly the same code I used previously to create the gdp data frame:

Here’s what the gdp_with_bosnia data frame looks like:

gdp_with_bosnia# A tibble: 5 × 4

Country `1952` `1972` `1992`

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Afghanistan 779. 740. 649.

2 Albania 1601. 3313. 2497.

3 Algeria 2449. 4183. 5023.

4 Angola 3521. 5473. 2628.

5 Bosnia and Herzegovina 974. 2860. 2547.Now take the gdp_with_bosnia data frame and create a table with the Country column center-aligned. In the table in Figure 5.7, it’s hard to scan the country names, and that center-aligned column just looks a bit weird.

This is another example where you have to change the gt defaults to mess things up. In addition to right-aligning numeric columns by default, gt left-aligns character columns. As long as you don’t touch anything, you’ll get the alignment you’re looking for.

If you ever do want to override the default alignments, you can use the cols_align() function. For example, here’s how to make the table with center-aligned country names:

gdp_with_bosnia %>%

gt() %>%

tab_style(

style = cell_borders(color = "transparent"),

locations = cells_body()

) %>%

tab_style(

style = cell_text(weight = "bold"),

locations = cells_column_labels()

) %>%

cols_align(

columns = "Country",

align = "center"

)The columns argument tells gt which columns to align, and the align argument selects the alignment (left, right, or center).

Use the Correct Level of Precision

In all of the tables you’ve made so far, you’ve used the data exactly as it came to you. The data in the numeric columns, for example, extends to four decimal places—almost certainly too many. Having more decimal places makes a table harder to read, so you should always strike a balance between what Jon Schwabish describes as “necessary precision and a clean, spare table.”

Here’s a good rule of thumb: if adding more decimal places would change some action, keep them; otherwise, take them out. In my experience, people tend to leave too many decimal places in, putting too much importance on a very high degree of accuracy (and, in the process, reducing the legibility of their tables).

In the GDP table, you can use the fmt_currency() function to format the numeric values:

table_bold_header %>%

fmt_currency(

columns = c(`1952`, `1972`, `1992`),

decimals = 0

)The gt package has a whole series of functions for formatting values in tables, all of which start with fmt_. This code applies fmt_currency() to the 1952, 1972, and 1992 columns, then uses the decimals argument to tell fmt_currency() to format the values with zero decimal places. After all, the difference between a GDP of $779.4453 and $779 is unlikely to lead to different decisions.

This produces values formatted as dollars. The fmt_currency() function automatically adds a thousands-place comma to make the values even easier to read (Figure 5.8).

Save your table for reuse as table_whole_numbers.

Use Color Intentionally

So far, our table hasn’t used any color. We’ll add some now to highlight outlier values. Especially for readers who want to scan your table, highlighting outliers with color can help significantly. Let’s make the highest value in the year 1952 a different color. To do this, we again use the tab_style() function:

table_whole_numbers %>%

tab_style(

style = cell_text(

color = "orange",

weight = "bold"

),

locations = cells_body(

columns = `1952`,

rows = `1952` == max(`1952`)

)

)This function uses cell_text() to change the color of the text to orange and make it bold. Within the cells_body() function, the locations() function specifies the columns and rows to which the changes will apply. The columns argument is simply set to the year whose values are being changed, but setting the rows requires a more complicated formula. The code rows =1952== max(1952) applies the text transformation to rows whose value is equal to the maximum value in that year.

Repeating this code for the 1972 and 1992 columns generates the result shown in Figure 5.9 (which represents the orange values in grayscale for print purposes).

The gt package makes it straightforward to add color to highlight outlier values.

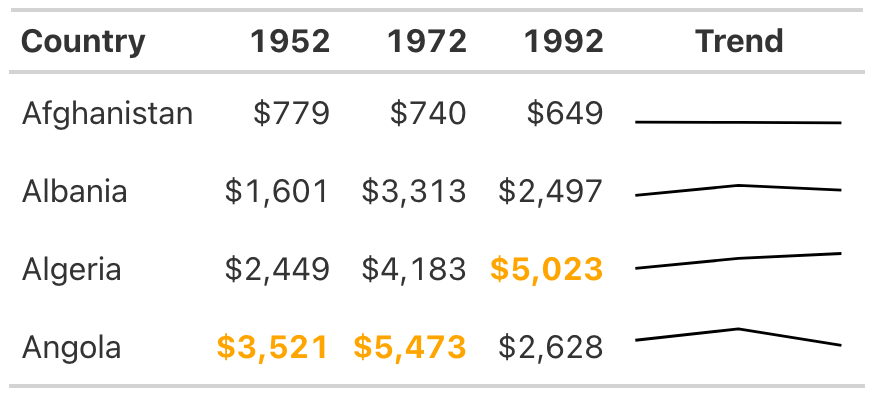

Add a Data Visualization Where Appropriate

Adding color to highlight outliers is one way to help guide the reader’s attention. Another way is to incorporate graphs into tables. Tom Mock developed an add-on package for gt called gtExtras that makes it possible to do just this. For example, say you want to show how the GDP of each country changes over time. To do that, you can add a new column that visualizes this trend using a sparkline (essentially, a simple line chart):

The gt_plt_sparkline() function requires you to provide the values needed to make the sparkline in a single column. To accomplish this, the code creates a variable called Trend, using group_by() and mutate(), to hold a list of the values for each country. For Afghanistan, for example, Trend would contain 779.4453145, 739.9811058, and 649.3413952. Save this data as an object called gdp_with_trend.

Now you create your table as before but add the gt_plt_sparkline() function to the end of the code. Within this function, specify which column to use to create the sparkline (Trend) as follows:

gdp_with_trend %>%

gt() %>%

tab_style(

style = cell_borders(color = "transparent"),

locations = cells_body()

) %>%

tab_style(

style = cell_text(weight = "bold"),

locations = cells_column_labels()

) %>%

fmt_currency(

columns = c(`1952`, `1972`, `1992`),

decimals = 0

) %>%

tab_style(

style = cell_text(

color = "orange",

weight = "bold"

),

locations = cells_body(

columns = `1952`,

rows = `1952` == max(`1952`)

)

) %>%

tab_style(

style = cell_text(

color = "orange",

weight = "bold"

),

locations = cells_body(

columns = `1972`,

rows = `1972` == max(`1972`)

)

) %>%

tab_style(

style = cell_text(

color = "orange",

weight = "bold"

),

locations = cells_body(

columns = `1992`,

rows = `1992` == max(`1992`)

)

) %>%

gt_plt_sparkline(

column = Trend,

label = FALSE,

palette = c("black", "transparent", "transparent", "transparent", "transparent")

)Setting label = FALSE removes text labels that gt_plt_sparkline() adds by default, then adds a palette argument to make the sparkline black and all other elements of it transparent. (By default, the function will make different parts of the sparkline different colors.) The stripped-down sparkline in Figure 5.10 allows the reader to see the trend for each country at a glance.

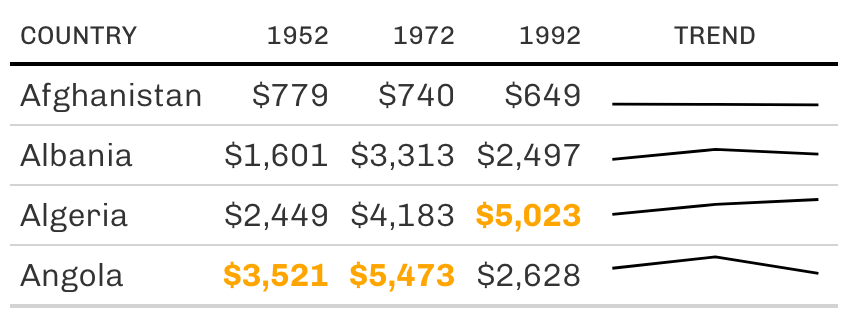

The gtExtras package can do much more than merely create sparklines. Its set of theme functions allows you to make your tables look like those published by FiveThirtyEight, the New York Times, the Guardian, and other news outlets.

As an example, try removing the formatting you’ve applied so far and instead use the gt_theme_538() function to style the table. Then take a look at tables on the FiveThirtyEight website. You should see similarities to the one in Figure 5.11.

Add-on packages like gtExtras are common in the table-making landscape. If you’re working with the reactable package to make interactive tables, for example, you can also use the reactablefmtr to add interactive sparklines, themes, and more. You’ll learn more about making interactive tables in Chapter 9.

Summary

Many of the tweaks you made to your table in this chapter are quite subtle. Changes like removing excess grid lines, bolding header text, right-aligning numeric values, and adjusting the level of precision can often go unnoticed, but if you skip them, your table will be far less effective. The final product isn’t flashy, but it does communicate clearly.

You used the gt package to make your high-quality table, and as you’ve repeatedly seen, this package has good defaults built in. Often, you don’t need to change much in your code to make effective tables. But no matter which package you use, it’s essential to treat tables as worthy of just as much thought as other kinds of data visualization.

In Chapter 6, you’ll learn how to create reports using R Markdown, which can integrate your tables directly into the final document. What’s better than using just a few lines of code to make publication-ready tables?

Additional Resources

Thomas Mock, “10+ Guidelines for Better Tables in R,” The MockUp, September 4, 2020, https://themockup.blog/posts/2020-09-04-10-table-rules-in-r/.

Albert Rapp, “Creating Beautiful Tables in R with {gt},” November 27, 2022, https://gt.albert-rapp.de.

Jon Schwabish, “Ten Guidelines for Better Tables,” Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis 11, no. 2 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1017/bca.2020.11.